Ebook features:

Bonus novella included

Read on any ereader, tablet or phone

Money back guarantee

Author Louise Mayberry

The Complete Darnalay Castle Series (Ebook)

The Complete Darnalay Castle Series (Ebook)

Transportive history

Transportive history

Literary quality writing

Literary quality writing

- Heartrending romance

Delivered instantly

Delivered instantly

Couldn't load pickup availability

In a century carved by empire and cruel ambition, love is the most dangerous rebellion of all.

From Glasgow’s smoke-dark alleys to Mexico’s storm-tossed shores and the rugged isolation of colonial Australia, this epic historical romance series will sweep you away, capture your heart and transport you to a different time.

This isn’t polished period fluff. It’s history with grit beneath its fingernails, and romance that will make your heart both ache and soar.

For readers who crave richly layered worlds, and stories that make you think and feel in equal measure.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

"A compelling story full of love, secrets, pain and hope that is as riveting as it is heart wrenchingly full of historic truths. I couldn’t put it down."

- Holly, website reviewer

What you’ll get in this ebook bundle:

Four full novels and one bonus novella, each filled with evocative historical settings, richly drawn characters, and heartrending, steamy romance.

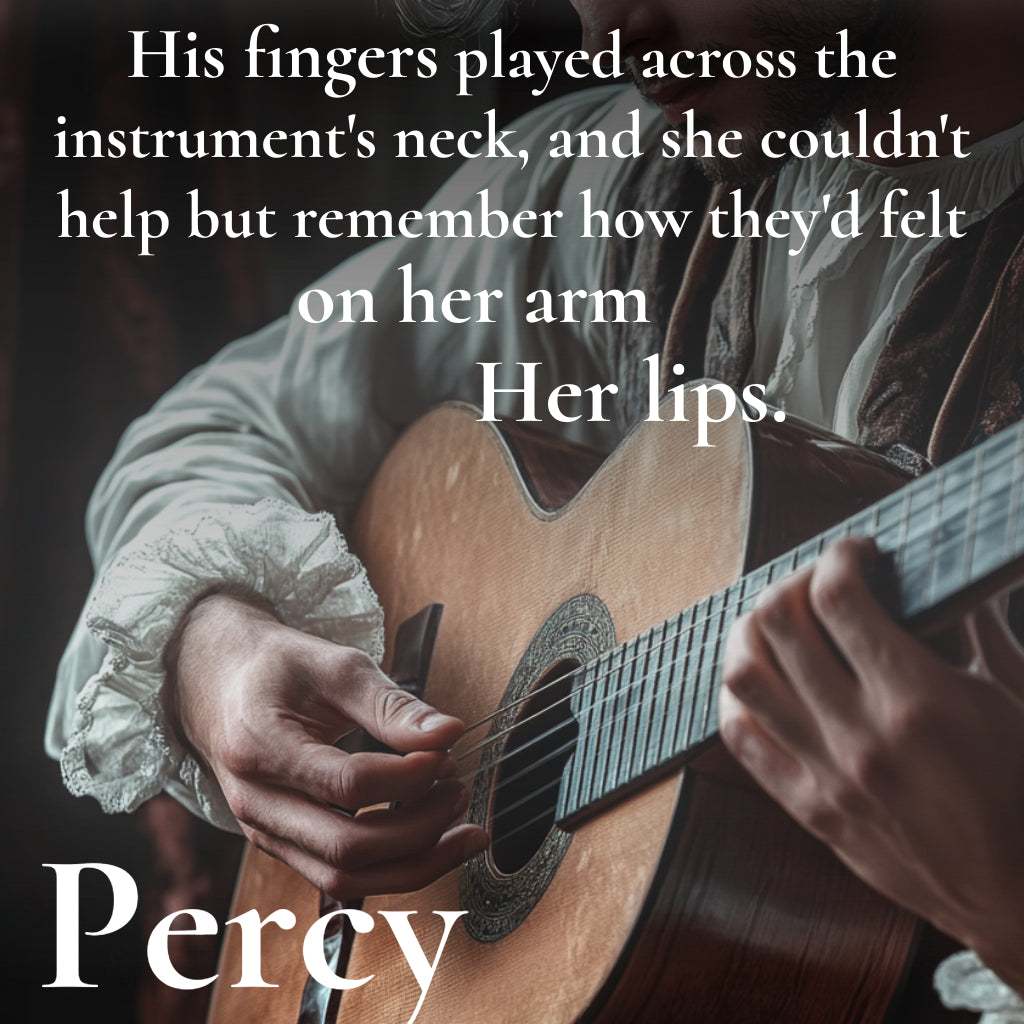

🌹 Roses in Red Wax - A grieving Highland beauty and a free-spirited musician forge a irresistible connection as the smoke of Glasgow’s spinning mills sparks a violent radical rebellion.

🌹 Swept Into the Storm – A shipwrecked earl and a determined abolitionist forge an unexpected bond under a blazing tropical sun.

🌹 A Radical Affair – Forbidden passion ignites when two souls on opposite sides of society risk it all for an impossible future.

🌹 The Song of the Magpie – An Irish widow and a tormented convict find redemption and hope in the rugged Australian frontier.

🌹 A Portrait of a Highlander – A haunting view of the spirit of the Highlands, where a stolid Highlander and an inspired painter discover a love they never dreamed possible.

What readers are saying:

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ "Reading this book was like being transported to Scotland 200 years ago." - Nira, Website reviewer

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ "I simply adore this series! I was hooked from the moment I started and couldn’t put it down!" - Emily, Goodreads reviewer

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ "This book is utterly wonderful. I’m currently on the last page, tears streaming down my face." - Apple Books reviewer

Ebook Details:

1: Roses in Red Wax. (282 pages)

2: Swept Into the Storm. (270 pages)

3. A Radical Affair. (262 pages)

4. The Song of the Magpie. (252 pages)

4.5. A Portrait of a Highlander - Bonus novella. (127 pages)

This bundle is not available anywhere else.

Read the full book descriptions

Read the full book descriptions

The Darnalay Castle Series

Step into the early industrial age—a world of radicals and romantics, capitalists and aristocrats—in these evocative, ground-breaking historical romances.

Book 1: Roses in Red Wax

1820 Scotland. All she wanted was to be left alone with her grief. Then he came along.

🌹A mysterious Highland beauty

🌹A sensual, free spirited musician

🌹A world descending into chaos

LOOK INSIDE

Book 2: Swept Into the Storm

1824 Mexico. He was looking for purpose, but he found so much more...

🌹A shipwrecked earl

🌹A woman determined to change the world

🌹A voyage that will reshape their destiny

LOOK INSIDE

Book 3: A Radical Affair

1824 Scotland. Her life was a prison. He could never escape his past.

🌹An illicit affair

🌹A desperate plan

🌹An impossible future

LOOK INSIDE

Book 4: The Song of the Magpie

1826 Australia. His assignment was to teach her to read, but they both learned so much more.

🌹A woman who dares to dream

🌹A man who's lost all hope

🌹A year of impossible peace

LOOK INSIDE

-

"Masterful writing, clever plots, deeply emotional and sizzling romance, compelling characters, and meticulously researched novels that are impossible to put down." - Helen

-

"A wild journey, riding the waves of pure, unadulterated emotion." - Kesha

-

"The author is not afraid of unconventional situations, characters, or outcomes, and it just works. This makes for such amazing stories to read." - Suzanne

About Me

Hi there! I'm Louise. I write steamy historical novels that blur the lines between romance and historical fiction.

I believe in the transportive power of love, and I'm fascinated by the connection between the past and the present - how threads that were spun hundreds of years ago are still woven into the fabric of our lives today.

My stories are angsty and steamy and full of adventure... and of course they always end with a happily ever after.♥️

How to Get the Books:

🛒 Add to cart

✉️ Check your email

📱Add to your tablet or e-reader

💺 Curl up in your favorite chair

🌹Lose yourself in the story

A Different Kind of Historical Romance

-

Transportive History

"The scenery and setting are developed in a way that guides the reader to envisage, smell, and feel nineteenth century Scotland as if it waits to greet them outside the front door." - Tim

-

Literary Quality

"Mayberry’s books are unique in the way they meet at the intersection of romance, historical fiction, and literature. Her writing is exquisite and layered." - Helen

-

Heartrending Romance

"So good I needed to take a reading break for a couple of days so I could put the pieces of my heart back together." - Amy

Frequently Asked Questions

How will I get my books?

Your books will be delivered via email by the industry standard eBook delivery service, BookFunnel.

Directly after you place your order, you'll receive an email from BookFunnel that will walk you through the steps to quickly and easily download your books to any eReader and/or listening devise.

Or, you can keep things simple and read or listen directly on the BookFunnel app without downloading at all!

If you run into any trouble along the way, BookFunnel support is ready and waiting to help - or you can contact me directly at louise@louisemayberry.com.

What if I have trouble accessing my books?

Most readers find downloading eBooks from BookFunnel to be a breeze. However, if you run into trouble, I'm here to help!

If you have questions or concerns at ANY time during the process, be sure to reach out to me via email: louise@louisemayberry.com. I always respond within 24 hours - usually much faster than that!

What if I don't like the books? Can I return them?

Because eBooks and audiobooks are downloaded files, they can't be returned after delivery.

However, if you are unhappy with your purchase for any reason, you may request a full, no-questions-asked refund within 30 days of your purchase.

What's the steam level?

Each book in this series contains several open-door sex scenes, as well as other explicit scenes and references.

Are there any content warnings I should know about?

Roses in Red Wax includes graphic descriptions of child labor, dire poverty, forced isolation and the grief that comes from the death of loved ones.

Swept Into the Storm includes descriptions of chattel slavery, oppression of Native Americans and racially motivated violence.

A Radical Affair includes discussion of abortion as well as descriptions of physical and psychological abuse, infidelity and the terrible prospect of two parents being forcibly separated from their newborn child.

The Song of the Magpie includes discussion of prostitution, miscarriage, physical abuse by law enforcement and forced eviction.

Have a question that isn't answered above? Send me and email! I always respond within 24 hours, usually much faster than that. louise@louisemayberry.com