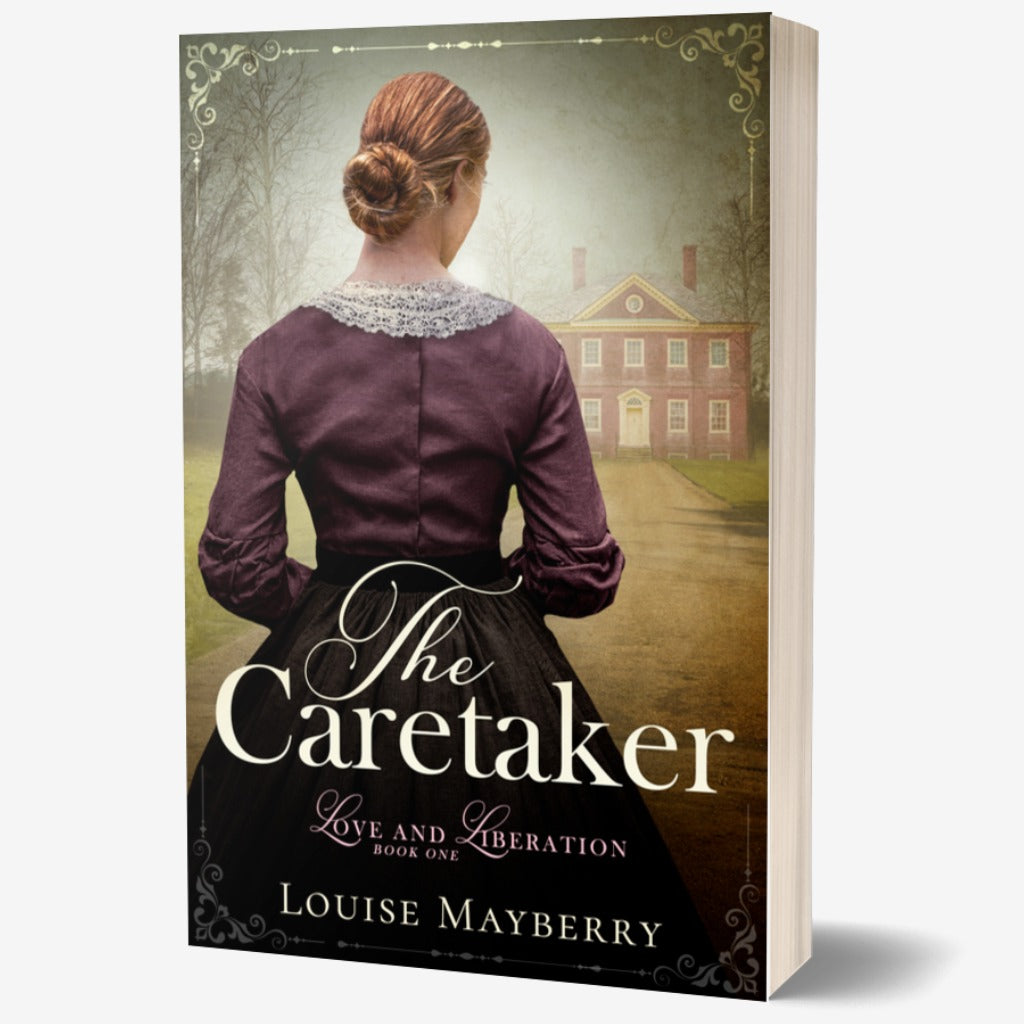

The Caretaker

New York State, 1841

...ALL WAS STILL, AS suited the hour. The waning moon just peered above a clear horizon; while from a couple of lanterns in the tower of the North Church, the beacon streamed to the neighboring towns, as fast as light could travel.

A little beyond Charleston Neck, Paul Revere was intercepted by two British officers on horseback; but being himself well mounted, he turned suddenly, and—

“Bridge ahead!”

Pritchett’s rasping call jerked Charley out of the cool Boston night and back into the glaring heat of the New York summer. He blinked up from his book. The span of wood and metal loomed, only a few feet away and drawing closer. He threw himself to the side to avoid getting bashed in the head. His neck stretching painfully, and his body cramped as the canalboat slid under the belly of the bridge. His hat fell, but when he reached for it, his fingers met only air.

Damn it.

“Couldn’t a’ warned me sooner, you old cur?” he muttered into the darkness.

They came out the other side, and he pushed himself back to sitting, only to spot his hat teetering at the edge of the roof, just about to tumble into the canal. He set the book on his lap and snatched it up, then ran his fingers through his hair, letting the breeze cool his sweaty scalp. What time was it anyway?

He glanced over his shoulder. The sun, which had been blazing high overhead when he’d first sat down to read, had melted into a smooth golden disk, sinking fast. And the scenery had changed too. The barren, drained swampland with its skeletons of trees had given way to dusty streets and low wooden warehouses. A packet boat—a rusty old one with a crowd of people on the roof—glided toward them, and beyond it, he could just make out the towering brick buildings of Utica through the haze.

Hang it all. The entire afternoon had slipped by. All those glorious, uneventful miles of the Long Level, with no locks and scarcely any bridges to interrupt…

His eyes wandered back to the page. To that Boston night of seventy years ago. The yellow lanternlight gleaming on the water, the dull thud of hooves galloping over the dirt road…

He closed the book. Pulled on his hat.

The Utica weigh-dock was just minutes ahead. The captain, Pritchett, had been complaining about the levels on his whiskey jug, and he’d be keen to slink away and fill it. That would leave Charley to drive the Maggie Lynn through before he could get supper for him and Fritz. Even then, his work wouldn’t be finished. Once they’d cleared the city, it’d be Charley’s turn to drive the mules through to the next lock in Frankfurt.

He wouldn’t get back to Paul Revere and that moonlit Boston night until tomorrow morning at the earliest.

The packet’s peeling paint glared gold in the afternoon sun. Charley squinted at the fading black letters that spelled out the craft’s name: Lucky Wren. But Charley could see no luck in it, only exhaustion and a stoic kind of hope. Tired, blank faces stared out the windows and down the canal. The crowd on the roof was so thick he could hardly make out one person from another. A woman, her face streaked with sweat, held a baby while a small girl leaned limp against her shoulder. A group of men in shirtsleeves sat on steamer trunks, smoking and playing cards. Laundry flapped in the breeze.

The men laughed, and the guttural sounds of some foreign language wafted on the breeze, cutting through the heavy air and the thick buzz of cicadas—German? Norwegian? He couldn’t tell from here.

Charley tucked his book under his arm, then turned back toward the prow. Pritchett stood at the helm, his right cheek bulging with tobacco, one hand on the tiller and the other clutching his whiskey jug. His bloodshot eyes met Charley’s, and they narrowed. “Shtay there,” he ordered.

Then he spat onto the deck.

Hell. The lusher had been guzzling whiskey the whole time Charley’d been reading.

“I shaid. Shtay.” The old man’s gaze held steady, though his head weaved back and forth.

Charlie fought the urge to roll his eyes. Of course. The packet boat. It would want the right of way—as was its due. It was headed west, packed with passengers and mail, while the Maggie only carried her cargo of wheat.

But Pritchett wouldn’t see it that way. In his view, every boat they passed was an enemy, and ceding the right of way meant losing some great war.

Charley pivoted until he was facing the oncoming craft once more, though he couldn’t bring himself to meet any of the passengers’ eyes.

He’d only taken this job after his previous captain had broken his leg and been forced to dock in Buffalo for the season. Charley had met Pritchett at a tavern. The old man had claimed he needed a bowsman and offered a decent wage. He was a drunk—that had been clear from the start—but a bloated captain was hardly a rarity on the canal. All in all, it had seemed a fair job… until that first afternoon, just above Lockport, when the real reason he’d hired Charley had become clear.

Just past Hitchen’s Bridge, they’d encountered a line boat headed west, weighed down with passengers and freight. Pritchett had demanded the right of way, and when the other captain, a young, rough-looking jack, refused to yield, Pritchett had sneered and spat into the canal. Then he’d ordered Charley to “change his mind”.

The old man had been mad as a meat axe when Charley refused to lift his fists, threatening to throw him off the boat in Lockport without pay. Charley had almost agreed. He was no man’s attack dog, but in the end, his need for a job and Pritchett’s need for a bowsman had won out, and they’d come to a mutually disagreeable agreement. Charley would stay on the Maggie, at least until they got to Albany. He wouldn’t slug anyone, but he would stand on the bow and look threatening.

And as much as he hated it, the idiotic show usually worked.

He crossed his arms and eyed the oncoming boat. It was so damn tempting to give the old badger the slip and disappear into the crowds of Utica, make his way back to Albany and find a better job to finish out the season. It would be easy.

Except Mam’s last letter from Maine gnawed at him. Her hand had been shaky and faint, and she’d mentioned feeling feeble—though she’d been irritatingly vague about the cause, assuring him she’d improve in no time. If she’d taken ill and couldn’t work, she’d need money for a doctor. Not to mention food, and the rent paid. His youngest sister, Hetty, still lived at home. She would need coin for schoolbooks and pencils.

He couldn’t afford to lose this job. Even if it meant putting up with the likes of Pritchett.

Their mule driver Fritz walked the towpath with the mules about fifty feet ahead, closing in on the driver from the opposing boat. The boy looked back, and Charley nodded, making the captain’s will known. Fritz grinned. Unlike Charley, the young shaver seemed to live for a fight. Thirteen at most, he spoke English but cursed in German, drank grog like a fish, and seemed eager to pummel anyone who looked at him wrong.

An apt apprentice for the captain.

“Let us pass!” Pritchett’s shout echoed across the canal. The oncoming boat’s bowsman shaded his eyes and studied the show of force: Fritz staring daggers at his driver; Charley—all six feet four inches and two hundred-twenty pounds of him—standing on the stable roof, arms crossed; and Pritchett, glowering drunkenly at the tiller.

The bowsman shrugged, then gestured to his driver to pull to the side so Fritz could pass.

Pritchett’s oily giggle rose from the stern. “Take that, ye weedy lil’ bitch.”

Charley felt his lips curl. What a fucking goney. All that to delay a boat full of tired women and children.

His performance finished, Charley jumped down onto the wooden planks that covered the cargo hold. He ignored the captain and the reek of whiskey as he rounded the helm. Then he descended the ladder into the cabin.

In here, the air was so close he could hardly breathe. Not that he wanted to. It stank of stale grog, piss, and tobacco… all the rank smells of Charley’s childhood. He had no idea how the captain slept in his filthy bunk. Charley only ever stored his things in the nook assigned to him. Much better to eat and bed down on the roof than in this hellhole.

Moving by rote in the dim space, he slipped the book into his knapsack, then climbed back out just as their mules passed the other boat’s driver. Fritz said something as he walked by, a taunt of some kind, to judge by his swagger. But the other boy had more sense than to take the bait. He gave no reply.

Charley shook his head. He’d tried to talk sense into Fritz, but it was no good. The young hellion would have to learn the hard way.

The Wren’s tow rope sank into the murk of the canal, and she slowed, moving only with her own momentum as the Maggie’s rope floated smoothly overtop. The other boat was mere feet away now, and Charley met the stare of the Wren’s bowsman, a pale, carrot-headed chap younger than Charley, but not by much. He grinned at the fellow and doffed his hat, doing his best to apologize for his captain’s assery with his cheeky expression. The young man’s brows knit in confusion, but it was too late to explain. They’d already passed each other, and the other boat was alongside.

Charley leaned against the rail, studying the canal ahead. They were still a half mile from the weigh-dock, but the queue of boats had already come into view. A wide laker, sitting low in the water under its cargo of grain, seemed to be the end of it. Charley took up the dock line, and—

“What the hell d‘ya think yer doin?” Pritchett’s scream ripped through the humid air.

What the—

Charley turned just as someone—a boy—leaped off the roof of the Maggie’s cabin and onto the deck, nearly knocking him down. A string of Pritchett’s curses trailed after him, though the captain couldn’t give chase. He was stuck at the tiller.

The boy, who must have come from the Wren, teetered at the rail, and Charley grabbed him by the collar. “Whoah, there.”

The lad shook him off. For a second, Charley thought he would jump—any sane person would with the captain boiling at him like that—but instead, the boy wheeled around and stared at Charley with round green eyes. Freckles dotted his skinny, sunburnt face, which was streaked with sweat and dirt. An old hat sat on his head, and tattered overalls covered a grimy, threadbare shirt. A wide leather belt looped around the boy’s waist, and… was that a sword?

A runaway. Had probably stowed away on the Lucky Wren and decided to cut out before he was caught.

Well, he’d chosen the wrong boat as his escape.

“Lovejoyyy.” Pritchett clung to the rudder, his face beaded with sweat as he practically jumped up and down in rage. “What the fuck are ye doin? Bring ‘im here.”

The lad’s eyes darted toward the captain, then back to Charley.

There was something unsettling about those eyes. Where had he seen them before?

“Goddamn it, man. What are ye doin’? Bring that punk, or I’ll… I’ll…”

Charley rounded the corner and pulled the lad into the shadow of the cabin. “You’ve got to jump,” he urged. “Get into the city. You can find a—”

“Are you Charley Lovejoy?”

Charley’s stomach did a flip. Who the hell was this? The boy looked eager, hopeful that Charley would say yes. And those unnerving green eyes…

But Charley hadn’t done anything wrong. And even if he had, it wasn’t as if the little tad could hurt him.

“Yea,” he answered reluctantly. “I’m Charley.”

The boy’s face spread into a wide smile. “Thank goodness.” He exhaled. “I’m—” He hesitated, the grin still tugging on his lips, as if he were stretching out the punchline of a jest. “I’m Hetty. Your sister.”

Pritchett rounded the corner, his face as red as a lobster. He was gripping a heavy iron bar with both hands.

The boy’s—no, Hetty’s—hand went to her sword hilt, and she began to pull the blade.

Two thoughts flashed through Charley’s mind at exactly the same time.

First, if somehow this boy standing before him was truly his baby sister Hetty, then she was his responsibility, his to protect.

Second, if Pritchett was drunk enough to leave the Maggie unmanned as they navigated into a city, he was also drunk enough to do any manner of ugly things.

The two truths collided, then combusted, and in the chaos of the explosion, Charley grabbed Hetty’s arm and pulled her toward the rail.

“Jump!” he yelled, and together they leaped off the side of the Maggie Lynn, and into the rancid green soup of the Erie Canal.