The Canterbury Female Boarding School

Share

This post was originally sent to my newsletter subscribers on April 24, 2025. Click here to subscribe.

I came across this amazing story as I was researching my next book - and it ended up inspiring a rather large part of the plot.

It begins in Canterbury, Connecticut in the 1830s.

This is Prudence Crandall:

Prudence was a Quaker, born in 1803 in Rhode Island. When she was 10, her family moved to Canterbury, Connecticut.

Prudence received the best education a girl could have hoped for at that time, attending a nearby Quaker school in Plainfield, then a boarding school in Rhode Island.

At age 23, she graduated and began a successful career as a teacher.

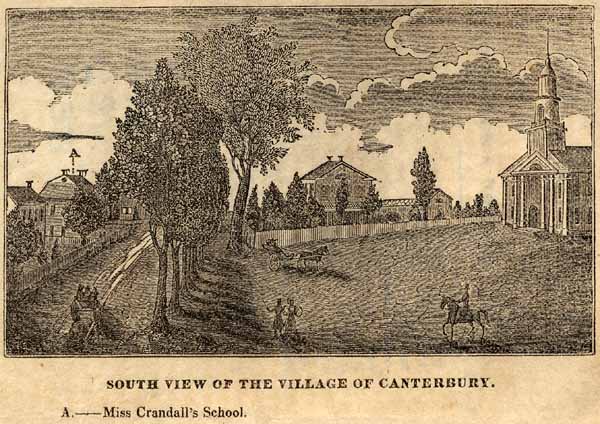

5 years later, in 1831, the wealthy residents of Canterbury requested that Prudence open a school for girls in the village. Because... "an unusual number of young girls then growing up in the village families awakened parental solicitude."

(Which I take to mean that there were a LOT of girls in the village. And their parents didn't know what to do with them.)

Prudence obliged. She purchased a large house in Canterbury and, along with her younger sister, set it up as a school for girls, teaching such subjects as reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, geography, history, chemistry, astronomy, and moral philosophy.

The building is still in existence:

All in all, things seemed to be going well.

In late 1831, Prudence hired a maid - a young Black woman named Mariah Davis.

Mariah's fiancé, Charles Harris, was the son of the local agent for the new abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator.

In late 1831, Prudence hired a maid - a young Black woman named Mariah Davis.

Mariah's fiancé, Charles Harris, was the son of the local agent for the new abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator.

(This paper, run by the great William Lloyd Garrison, would go on to be one of the driving forces in the growing abolitionist movement in the United States.)

Mariah read The Liberator, and passed copies on to Prudence, who was affected by the stories of the cruelty and evil of slavery. She wrote: "my sympathies are greatly aroused."

Mariah read The Liberator, and passed copies on to Prudence, who was affected by the stories of the cruelty and evil of slavery. She wrote: "my sympathies are greatly aroused."

Mariah also sometimes sat in on classes, which, as she was a maid and not officially a student, didn't seem to bother anyone.

But then, Mariah asked Prudence to admit Charles' sister, Sarah - a Black woman who dreamed of becoming a teacher and educating Black students.

But then, Mariah asked Prudence to admit Charles' sister, Sarah - a Black woman who dreamed of becoming a teacher and educating Black students.

After consulting with her bible, and her conscience, Prudence agreed.

Thus, the very first integrated school in America was created.

Thus, the very first integrated school in America was created.

And that bothered people.

The white townsfolk demanded that Prudence throw Sarah out, and when she steadfastly refused, they began pulling their own daughters out of the school.

But Prudence held fast.

As it became apparent that an integrated school in Canterbury was not feasible, she decided to abandon the idea, and to instead convert her school into one that would serve only "young Ladies and little Misses of color."

With the help of prominent abolitionists and free Black families, Prudence re-opened the school, and she was soon teaching a brood of 24 young Black women and girls from all over the North.

As you may guess, the townsfolk were outraged.

Here’s a description from the time of how they terrorized Prudence and her students:

They insulted and annoyed her and her pupils in every way their malice could devise. The storekeepers, the butchers, the milk-pedlers of the town, all refused to supply their wants; and whenever her father, brother, or other relatives, who happily lived but a few miles off, were seen coming to bring her and her pupils the necessaries of life, they were insulted and threatened. Her well was defiled with the most offensive filth [manure], and her neighbors refused her and the thirsty ones about her even a cup of cold water, leaving them to depend for that essential element upon the scanty supplies that could be brought from her father’s farm. Nor was this all; the physician of the village refused to minister to any who were sick in Miss Crandall’s family, and the trustees of the church forbade her to come, with any of her pupils, into the House of the Lord.

And it wasn’t only local opposition.

The Connecticut Legislature passed a ‘Black Law’ that specifically targeted the Canterbury Female Boarding School. It made it illegal to open a school for African Americans from out of state without the express permission of the town the school was to operate in.

Still, Prudence refused to close her school.

She was arrested, and though she could have avoided jail time by paying a fee, she refused to do so, writing: I am only afraid they will not put me into jail. Their evident hesitation and embarrassment show plainly how much they deprecate the effect of this part of their folly; and therefore I am the more anxious that they should be exposed, if not caught in their own wicked devices.

She spent one night in jail before she was released.

The trial of Prudence Crandall went all the way to the Connecticut Supreme Court, where it was thrown out on a technicality. Ultimately, it seems, the court didn’t rule on the case because they were afraid of the popular backlash if they were to rule in Prudence’s favor, and declare the truth: that the ‘Black Law’ was unconstitutional.

And so, Prudence went back to Canterbury where she continued teaching.

Then, on the night of September 9th 1834, just a week after Prudence’s 31st birthday, an angry mob attacked the school with clubs and iron bars, breaking windows and terrorizing the students. Fearing for their safety, Prudence finally made the decision to close the school.

She left Connecticut, and never returned.

It’s a sad ending, but it’s not really the end.

The story of the Canterbury Female Boarding School created a spark for the abolitionist movement.

As The Liberator and other papers covered the story, it captured the national attention and began to turn the tide against the bigotry that was so pervasive in the North, and toward the ideas of abolition and Black equality.

And of course, Prudence's legacy lived on in her students, many of whom went on to be influential figures in both the abolitionist and suffrage movements.

Perhaps there's a lesson for us, in all of this.

That sometimes failures aren't what they seem.

Click here to subscribe and join my community of readers.

My newsletter is an eclectic mix of stories I've uncovered in my historical research, thoughts and updates on writing and life, and other bits of beauty delivered to your inbox each Thursday. I hope to see you there!