Pulling the threads of history: The story of New Lanark

Share

This post was originally sent to my newsletter subscribers on April 11, 2025. Click here to subscribe.

My research process tends to be messy and somewhat tangential.

(I used to find that worrying, but it works, so I’ve learned to go with it.)

It goes something like this:

I read everything I can find about a period, paying particular attention to biographies. (I find the specifics of peoples’ lives much more interesting than the general overview found in most history books.) When I come across something that intrigues me, I pull on that thread, following it wherever it might lead.

Somewhere along the way, inspiration always seems to strike, and a story begins to form.

Today, I want to tell you about one of those historical threads - a life that doesn't actually show up in any of my books, but in many ways binds all my stories together.

It’s the story of Robert Owen.

Owen was born in Wales in 1771.

His father was a saddler and an ironmonger, and though young Robert loved to read, he had very little formal education.

As a teenager, he apprenticed as a draper, eventually moving to Manchester to pursue that trade.

It didn’t last long.

In Manchester, Robert became involved in the management of cotton spinning mills. He held Enlightenment views (probably due to all that reading he did as a boy), and over time he became more and more interested in how working conditions could be improved in the mills.

In the late 1790s, during a trip to Glasgow, Robert met Anne Caroline Dale, the daughter of mill owner and philanthropist, David Dale. The two fell in love and were married in 1799.

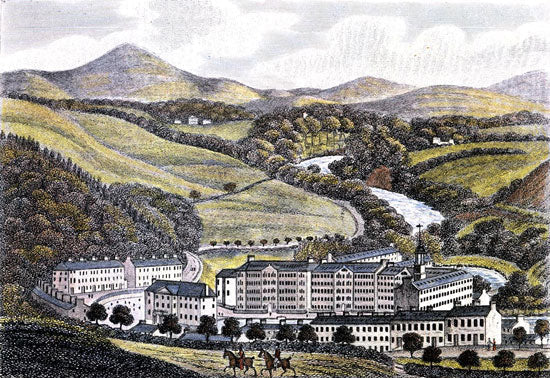

One of the largest mill complexes that Anne’s father owned was on the River Clyde, just 30 miles outside Glasgow. It was known as New Lanark. (You can see an image of it in the header of this email.)

Robert purchased New Lanark, and Robert and Anne made it their new home.

About 2,000 people lived and worked at New Lanark at the time, including 500 orphaned children from poorhouses in Glasgow and Edinburgh. And though David Dale was known for his benevolence and charity, Robert found the working conditions unsatisfactory.

He set to work reshaping New Lanark into something completely new - an efficient factory producing high quality thread and cloth, while also taking care of the health and welfare of its workers.

The model succeeded.

Over the next twenty years, New Lanark became a shining example of the possible. It was one of the largest textile mills in all of Britain, and one of the most visited, as people came from far and wide to see for themselves how a factory could be both efficient and humane.

New Lanark is where my research first intersected with Robert’s life. If you’ve read Roses in Red Wax, you’ll know that this idea of a more humane model of industrial production is a key point in the novel. New Lanark is even mentioned by name several times.

But that’s only the beginning of where Robert Owen's life connects to my work.

Through the 1810s and 20s, Robert became an advocate for the cessation of child labor and strengthened labor laws generally. He made many trips to London to advocate for this cause, and he developed many friendships with like-minded men.

One of those men - whom Robert reportedly visited quite often - was the Gothic novelist and political philosopher, William Godwin… None other than the father of Mary Shelley (author of Frankenstein and wife to the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley).

The discovery of this connection between the humane industrialist and the Gothic novelist who was father-in-law to Percy Shelley was electrifying for me, as it created real, historical grounds for the possibility of someone like my Percy—Percy Sommerbell, a humane industrialist and Romantic who, in many ways, was based on Shelley.

I thought I was done with Robert Owen, when he randomly popped up again as I was researching my most recent work, A Portrait of a Highlander.

One of the things Robert was most proud of at New Lanark was his education system. In addition to a primary school for older children, he created one of the first “infant schools” (similar to today’s Kindergartens).

The infant school included children from ages 2-6, and instead of being forced to sit and study from a book, as was the method of the time, Robert believed that young children should be able to lead their own education—to play together in nature, with mild guidance from a kind and caring adult, and to learn experientially.

(While that model may sound familiar to modern readers, in the nineteenth century, when corporeal punishment was the norm, it was quite radical.)

To lead his infant school, Robert turned to a man from the village, known not for his formal education, but for being good with children—James Buchanan.

By all accounts, Buchanan excelled in his role. He was a kind and gentle soul, and was able to lead the children to their own discoveries about the world in a way that had never before been seen in a school setting.

There's one lovely account of Buchanan leading the children on a romp through the woods, playing a flute, while the children danced behind.

In 1818, Ben Leigh Smith, a radical politician from Sussex, visited New Lanark. He was impressed with the infant school, and he persuaded James Buchanan to move south to teach at school he was involved in setting up.

In England, Buchanan ended up having a formative influence on Ben’s own young daughter: Barbara.

Barbara Leigh Smith (as you know if you’ve been reading this newsletter for some time), was a huge influence on me personally, and on the character of Gwen, in A Portrait of a Highlander.

(And speaking of personal influence, another thing Robert did at New Lanark was set up a store for the millworkers. It wasn't a typical company store - it was run by and for the workers, and it stocked high quality, nutritious foods and affordable prices.

This store was reportedly the inspiration for the first modern cooperative: The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, whose legacy can be traced directly to the food cooperatives that I myself worked in for twenty years.)

Anyhow, I know this is getting long, but there’s one more connection to tell you about.

This one brings Owen’s influence all the way to America, and the research I’ve been doing for my next book.

In 1824, Owen decided to move the New Lanark model to the United States, where he - along with his adult children - set up a utopian community in New Harmony, Indiana.

The community failed within a few years, and Robert returned to Scotland, but his children stayed in Indiana where they became influential citizens of the Republic.

His daughter Jane set up a school in New Harmony, using the same radical methods that Robert Buchanan pioneered.

His son David oversaw the first geological survey of my home state of Wisconsin.

Another son, Robert Dale was prominent in political circles, and advocated directly to Abraham Lincoln in favor of The Emancipation Proclamation.

Robert Dale Owen also penned this incredible proclamation on his wedding day...

While I can’t tell you exactly how any of these stories will come to play in my new series, you better believe they’ll be there somehow.

Owen was born in Wales in 1771.

His father was a saddler and an ironmonger, and though young Robert loved to read, he had very little formal education.

As a teenager, he apprenticed as a draper, eventually moving to Manchester to pursue that trade.

It didn’t last long.

In Manchester, Robert became involved in the management of cotton spinning mills. He held Enlightenment views (probably due to all that reading he did as a boy), and over time he became more and more interested in how working conditions could be improved in the mills.

In the late 1790s, during a trip to Glasgow, Robert met Anne Caroline Dale, the daughter of mill owner and philanthropist, David Dale. The two fell in love and were married in 1799.

One of the largest mill complexes that Anne’s father owned was on the River Clyde, just 30 miles outside Glasgow. It was known as New Lanark. (You can see an image of it in the header of this email.)

Robert purchased New Lanark, and Robert and Anne made it their new home.

About 2,000 people lived and worked at New Lanark at the time, including 500 orphaned children from poorhouses in Glasgow and Edinburgh. And though David Dale was known for his benevolence and charity, Robert found the working conditions unsatisfactory.

He set to work reshaping New Lanark into something completely new - an efficient factory producing high quality thread and cloth, while also taking care of the health and welfare of its workers.

The model succeeded.

Over the next twenty years, New Lanark became a shining example of the possible. It was one of the largest textile mills in all of Britain, and one of the most visited, as people came from far and wide to see for themselves how a factory could be both efficient and humane.

New Lanark is where my research first intersected with Robert’s life. If you’ve read Roses in Red Wax, you’ll know that this idea of a more humane model of industrial production is a key point in the novel. New Lanark is even mentioned by name several times.

But that’s only the beginning of where Robert Owen's life connects to my work.

Through the 1810s and 20s, Robert became an advocate for the cessation of child labor and strengthened labor laws generally. He made many trips to London to advocate for this cause, and he developed many friendships with like-minded men.

One of those men - whom Robert reportedly visited quite often - was the Gothic novelist and political philosopher, William Godwin… None other than the father of Mary Shelley (author of Frankenstein and wife to the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley).

The discovery of this connection between the humane industrialist and the Gothic novelist who was father-in-law to Percy Shelley was electrifying for me, as it created real, historical grounds for the possibility of someone like my Percy—Percy Sommerbell, a humane industrialist and Romantic who, in many ways, was based on Shelley.

I thought I was done with Robert Owen, when he randomly popped up again as I was researching my most recent work, A Portrait of a Highlander.

One of the things Robert was most proud of at New Lanark was his education system. In addition to a primary school for older children, he created one of the first “infant schools” (similar to today’s Kindergartens).

The infant school included children from ages 2-6, and instead of being forced to sit and study from a book, as was the method of the time, Robert believed that young children should be able to lead their own education—to play together in nature, with mild guidance from a kind and caring adult, and to learn experientially.

(While that model may sound familiar to modern readers, in the nineteenth century, when corporeal punishment was the norm, it was quite radical.)

To lead his infant school, Robert turned to a man from the village, known not for his formal education, but for being good with children—James Buchanan.

By all accounts, Buchanan excelled in his role. He was a kind and gentle soul, and was able to lead the children to their own discoveries about the world in a way that had never before been seen in a school setting.

There's one lovely account of Buchanan leading the children on a romp through the woods, playing a flute, while the children danced behind.

In 1818, Ben Leigh Smith, a radical politician from Sussex, visited New Lanark. He was impressed with the infant school, and he persuaded James Buchanan to move south to teach at school he was involved in setting up.

In England, Buchanan ended up having a formative influence on Ben’s own young daughter: Barbara.

Barbara Leigh Smith (as you know if you’ve been reading this newsletter for some time), was a huge influence on me personally, and on the character of Gwen, in A Portrait of a Highlander.

(And speaking of personal influence, another thing Robert did at New Lanark was set up a store for the millworkers. It wasn't a typical company store - it was run by and for the workers, and it stocked high quality, nutritious foods and affordable prices.

This store was reportedly the inspiration for the first modern cooperative: The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, whose legacy can be traced directly to the food cooperatives that I myself worked in for twenty years.)

Anyhow, I know this is getting long, but there’s one more connection to tell you about.

This one brings Owen’s influence all the way to America, and the research I’ve been doing for my next book.

In 1824, Owen decided to move the New Lanark model to the United States, where he - along with his adult children - set up a utopian community in New Harmony, Indiana.

The community failed within a few years, and Robert returned to Scotland, but his children stayed in Indiana where they became influential citizens of the Republic.

His daughter Jane set up a school in New Harmony, using the same radical methods that Robert Buchanan pioneered.

His son David oversaw the first geological survey of my home state of Wisconsin.

Another son, Robert Dale was prominent in political circles, and advocated directly to Abraham Lincoln in favor of The Emancipation Proclamation.

While I can’t tell you exactly how any of these stories will come to play in my new series, you better believe they’ll be there somehow.

Click here to subscribe and join my community of readers.

My newsletter is an eclectic mix of stories I've uncovered in my historical research, thoughts and updates on writing and life, and other bits of beauty delivered to your inbox each Thursday. I hope to see you there!