A love story that echoes through time...

Share

Someway, somehow, almost a year has passed since the publication of my second novel (and the second installment in the Darnalay Castle Series), Swept Into the Storm. May 5th marks the day. Given this auspicious event, I thought I’d spend the next few weeks diving into some of the little-known but fascinating stories I uncovered while researching that book and its setting of Latin America in the early nineteenth century.

Stories like this one, a tale that inspired me when I first read it, and continues to haunt me: the tragic love of Catherine and Edward Despard.

_________________

No pictures exist of Catherine. She was born in Jamaica, somewhere around 1755, the daughter of a free Black woman and an unknown white man. She was well educated, as her later life made clear, but how and by whom is lost to history.

Sometime in the 1780s, she met this man, Colonel Edward (Ned) Despard, an Irish officer in service to the British crown.

Ned was born in 1751, the youngest of eight siblings and the son of a wealthy landowner in Queen’s County, Ireland.

At age fifteen he joined the army, and was first stationed in Jamaica, where he worked as a defense works engineer, building bridges, roads, and fortifications. Later, he was sent to Guatemala to fight the Spanish, then to the Miskito Coast (present day Niceragua and Honduras) where he commanded his men in a decisive victory and attained the rank of colonel.

In all this time, Ned oversaw and worked with multi-racial work crews and troops—Black, white and Indian men all served under his command—and he became known for his ability to effectively inspire and organize these diverse groups.

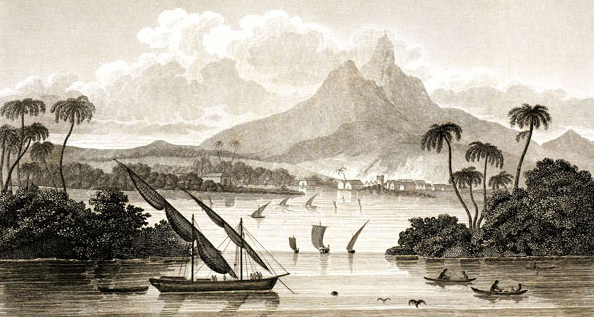

In 1783, he was made superintendent of the British settlement on the Bay of Honduras, a place which at that time was inhabited by wealthy British loggers, their enslaved workers and a growing population of free Blacks and landless white settlers.

This is where Ned’s story gets interesting. And though it's not known exactly where they met or when they married, I like to think that this is where Catherine’s influence in his life begins to show itself.

As superintendent of The Settlement, Ned made a point of treating all settlers equally, regardless of their “age, sex, character, respectability, property or colour.” Much to the dismay of the wealthy elite, he distributed land by lottery, giving free Blacks the same chance of acquiring property as white settlers. And that wasn’t all. He also set aside large swaths of land for common use and put measures into place to keep food affordable for those without means.

While this may sound like sound governance to our modern sensibilities, in the 1780s it was radical behavior. Fearing an upset to their dominance, the wealthy white loggers complained to the government in Britain, and in 1790, Ned was recalled to England for an inquiry. After twenty years abroad, he and Catherine, along with their young son James, traveled to London.

Once there, Ned was embroiled in expensive lawsuits brought by his enemies in Honduras. He was denied a pension by the army, and spent two years in debtor’s prison, where he read the work of the revolutionary democratic thinker, Thomas Paine. After his release, he became a prominent figure in the Irish freedom movement, and was imprisoned without charge for three years under a suspension of habeas corpus. After he was finally freed, he (allegedly) became involved in a plot to assassinate the king in order to make way for a democratic republic to form in England. And it was for this - though the jury found there wasn’t enough evidence to convict - that he was, in 1803, sentenced to death.

And where was Catherine during these years? Was she, a Black woman in London, sitting at home demurely doing needlepoint? I think not. She was tirelessly, publicly and eloquently petitioning for her husband. Outraged by the conditions Ned was held in, she became involved in the prison reform movement, and she loudly demanded that habeas corpus be reinstated. Her words were read on the floor of the House of Commons during a debate on the matter, and they must have been good words, because they elicited this comment from the attorney general:

"It was a well-written letter, and the fair sex would pardon him, if he said it was a little beyond their style in general."

Catherine was described by Admiral Nelson (military hero, past army associate of Despards and friend of the family) as being “violently” in love with her husband, and her reaction to the news of Ned’s death sentence was described by the press as:

“... impossible to describe. The composure she had hitherto preserved could no longer resist the conflict of her feelings. She was at length carried to a coach, in a state of grief and agitation bordering on distraction.”

But she regained her composure, and her outward strength. During Ned’s last days, she was a frequent visitor to the gaol where he was held as together, they drafted the speech he would give at the gallows. She must have been a fiery and forceful presence, because the night of the execution, after detailing a long list of concerns about violence and rioting, the chief magistrate of London concluded a letter to the Home Secretary with these words:

‘Mrs. Despard has been very troublesome, but at last she is gone away.’

I know this post is getting long, but please, read Ned and Catherine’s speech. These are the words they wrote together, and which he delivered to the 20,000 Londoners (the largest crowd ever assembled at that time) who came to watch his execution. It gives me chills each time I read it, as if their words are echoing through time, meant for my ears.

Fellow Citizens, I come here, as you see, after having served my Country faithfully, honourably and usefully, for thirty years and upwards, to suffer death upon a scaffold for a crime of which I protest I am not guilty. I solemnly declare that I am no more guilty of it than any of you who may be now hearing me. But though His Majesty’s Ministers know as well as I do that I am not guilty, yet they avail themselves of a legal pretext to destroy a man, because he has been a friend to truth, to liberty, and to justice

[a considerable huzzah from the crowd]

because he has been a friend to the poor and to the oppressed. But, Citizens, I hope and trust, notwithstanding my fate, and the fate of those who no doubt will soon follow me, that the principles of freedom, of humanity, and of justice, will finally triumph over falsehood, tyranny and delusion, and every principle inimical to the interests of the human race.

[a warning from the Sheriff]

I have little more to add, except to wish you all health, happiness and freedom, which I have endeavoured, as far as was in my power, to procure for you, and for mankind in general.

After Ned’s death, Catherine’s history again fades into the unknown. We do know that she was denied a pension, probably because of the inflammatory nature of her husband’s last words - especially his use of the term “human race,” with its implication of the inherent equality of everyone who is human.

Presumably, she was cared for by friends and associates until her death in London in 1815. James, their son, went to France and became a soldier. After that, his story also fades away.

After Ned’s death, Catherine’s history again fades into the unknown. We do know that she was denied a pension, probably because of the inflammatory nature of her husband’s last words - especially his use of the term “human race,” with its implication of the inherent equality of everyone who is human.

Presumably, she was cared for by friends and associates until her death in London in 1815. James, their son, went to France and became a soldier. After that, his story also fades away.

_________________

I’m curious, what does this story bring up for you? For me, there are two things:

The first is a sadness that so much of Catherine’s story is lost, and that almost everything we know about her - this incredible woman of color - is in reference to her white husband.

The second is the hard fact that (though I love my happily-ever-afters), in “real” history, so often the endings are not happy at all. They’re tragic. Catherine watched her beloved die a horrible death, then she lived her last years alone in a foreign land, probably destitute.

And yet, the ideas she and Ned stood for, what they fought for, lives on.

How I wish I could go back in time, to the grieving Catherine Despard, and tell her that.